The Queen Mother of the West (Xi-Wang-Mu) is one of the most complex and enduring goddesses in Chinese mythology, whose identity and imagery have evolved over thousands of years. She began as a powerful and independent goddess associated with nature, death, and cosmic balance in early Chinese creation myths and was later institutionalized within Daoist religion and popular folklore.

Archetype

In early mythology and oracle bone inscriptions, the terms “Eastern Mother” (Dong Mu) and “Western Mother” (Xi Mu) are associated with her and are considered among the earliest written records referencing her. She appears as a goddess linked to the setting sun, death, and fertility. Her early form included animalistic features such as tiger teeth and a leopard tail—symbols likely representing divine deterrence or cosmic authority rather than literal monstrosity. However, many later artistic works interpreted these as literal physical features. For example, in the Ming dynasty, Wang Zongqing’s engraved interpretation of the Classic of Mountains and Seas depicts the Queen Mother of the West with a tiger’s tail.

Pre-Qin era

By the pre-Qin era, texts such as the Classic of Mountains and Seas, Mu Tianzi Zhuan, and Zhuangzi portrayed her as a divine ruler residing on Mount Kunlun, possessing three-legged birds, mystical powers, and the ability to foresee disasters. In Zhuangzi, she is described as a possessor of the Dao, embodying the ultimate cosmic principle. She also symbolized autumn, the moon, and decline—concepts traditionally associated with the western direction in ancient cosmology.

Western Han Dynasty

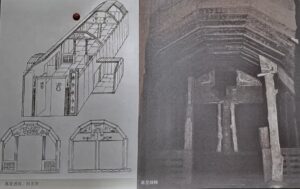

During the Western Han Dynasty, she became central to the pursuit of immortality and was believed to possess the elixir of life. As a result, she was often placed in a central or elevated position in Han dynasty tomb murals and stone reliefs. In a mural from the Xin Mang period (around the turn of the first century CE), discovered in a tomb in Luoyang, Henan, she is positioned above the passage leading to the main burial chamber (Fig. 6). This mural features rabbits, toads, and nine-tailed foxes—symbols not recorded in ancient texts. The rabbit and toad connect her to the moon, while the rabbit, shown pounding medicine, symbolizes her association with the elixir of life. The nine-tailed fox, as noted by Li, represents the deceased’s wish for protection over their family and the continuation of family ties after death. During this period, the Queen Mother of the West retained her divinity and independence. She also served as a symbol of the Han people’s hopes and aspirations, leading to the addition of new elements to her original mythology. The worship of the Queen Mother of the West reached its peak during this time.

Eastern Han Dynasty

By the Eastern Han period, the Queen Mother was often depicted seated on a throne flanked by the Azure Dragon and White Tiger—symbolic mounts of the east and west—alongside other recurring elements such as three-legged birds, rabbits, and nine-tailed foxes. She is also described in Han immortality texts as the host of the mythical Peach Banquet. Thus, her image became more diverse and complex in the Han dynasty than in earlier periods.

Daoism

As Daoism developed, she was integrated into the celestial hierarchy as the highest-ranking female immortal and was often paired with the King Father of the East to represent yin-yang duality. A notable example is found in the Eastern Han tomb gate from Beizhai, Yinan County, Shandong Province, where the King Father of the East appears on the eastern gate and the Queen Mother of the West on the western gate. However, this pairing also led to a loss of her earlier independence, as she began sharing divine authority with male counterparts.

The Leader of Female Immortals

After the Han dynasty, China experienced roughly 360 years of political fragmentation until reunification under the Sui dynasty. During this period, the Queen Mother gradually lost her prominence in religious belief and survived only within Daoist traditions as a female immortal. Today, the most complete surviving Daoist ritual mural featuring her is found in Yongle Palace. On the east wall of the Sanqing Hall, she is portrayed as a regal empress seated on a throne, richly adorned with celestial symbols—such as the phoenix, jade maidens, and peaches, each containing a rabbit. However, there is still scholarly debate over whether she is depicted on the east or west wall of the hall, indicating that her divine identity and veneration have faded over time.

Folklore

In later folklore, her image became increasingly popularized and simplified. She was known as Wangmu Niangniang, a benevolent, empress-like figure associated with celestial peaches, weddings, and immortality. Yet in some stories, such as The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, she appears as an antagonist, reflecting her shifting status and the broader cultural marginalization of powerful female figures.

Looking at the queen mother of the west historical trajectory, in the early stages of human civilization, the Queen Mother of the West undeniably held an essential and powerful position. Yet, as society progressed and patriarchal structures solidified, she gradually lost her independence as a solemn and authoritative goddess. Her appearance was altered to be more youthful, her status as the highest-ranking female immortal was reduced to that of the wife of the most powerful male deity, making her subordinate to male authority. Under the influence of religious integration with imperial authority, the Queen Mother of the West temporarily disappeared from Daoist rituals and temple murals. In folk tales, she was even cast as a villain who obstructed love, further marginalizing her divine presence. The later image of the Queen Mother of the West in folklore had largely diverged from her depiction in pre-Qin mythology and Han dynasty records.

》十八卷-226x300.jpg)