· Three Azure Birds or Three-Legged Birds

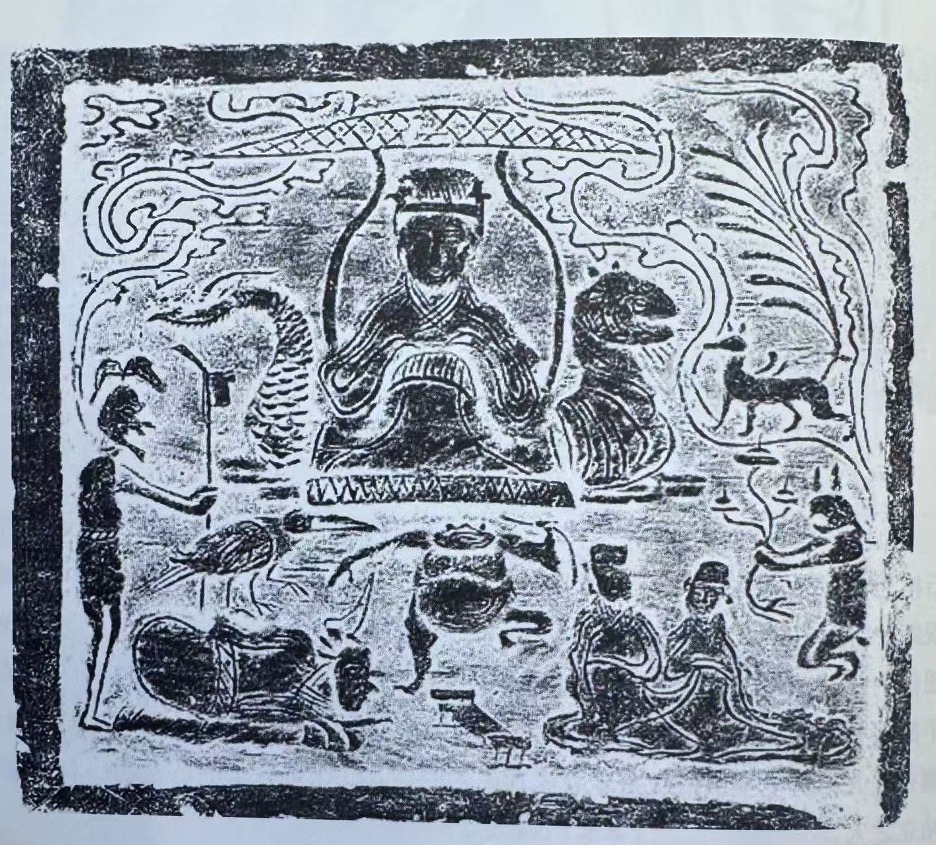

The Three Azure Birds are among the most distinctive and enduring symbols associated with Xiwangmu, appearing prominently in early Chinese mythology and continuing into Han dynasty visual culture. In later imagery, they gradually evolved into three-legged birds. In the Hai Nei Bei Jing section of the text, the birds are described as residing to the south of her seat and are responsible for gathering food for her, emphasizing their role as divine attendants. This intimate and service-oriented relationship suggests not only the Queen Mother’s elevated status but also her integration into a larger cosmic and ecological order.

The presence of the Three Azure Birds reinforces her connection to Kunlun Mountain and the heavenly realm. In visual representations from the Han dynasty, these birds are depicted hovering above or beside her, sometimes linked together, highlighting their ritual and symbolic importance. As messengers and intermediaries between realms, they underscore the Queen Mother’s sovereignty over life, death, and immortality. Their recurring appearance in both texts and tomb art also reflects their deep-rooted role in ancient Chinese belief systems, representing vitality, divine nourishment, and spiritual mediation within her mythological iconography.

· Phoenix

The phoenix holds an enduring symbolic connection with the Queen Mother of the West, reflecting her divine authority, celestial status, and role as the bestower of immortality. This relationship can be traced back to early textual sources such as the Shan Hai Jing, where the phoenix—also referred to as the green bird—was originally described as serving her even before her transformation into a fully deified figure. As her cult evolved during the Eastern Han dynasty, the phoenix was reimagined as her celestial attendant, vehicle, or messenger, reinforcing her elevated position within the Daoist pantheon.

Furthermore, in the Huainanzi, the Queen Mother is described in exquisite detail, wearing phoenix-patterned shoes, a crown adorned with celestial motifs, and a brocade robe radiating brilliance. This imagery casts her as a luminous, youthful goddess seated in majesty among a court of immortals. The presence of the phoenix in both her attire and her visual environment emphasizes her commanding grace and reinforces her identity as a sovereign of the immortal realm. Thus, the phoenix becomes a key icon in visually articulating her divine rank, spiritual refinement, and timeless beauty.

In Yuan dynasty Daoist murals, such as those found in Yongle Palace, the phoenix continues to appear prominently alongside the Queen Mother of the West, maintaining its independent stature while other symbols like the hare and peaches are reduced to ornamental motifs. This may be because the phoenix is also associated with the image of the empress in the imperial court.

· Jade Hare

The Jade Hare is a key symbolic companion of Xiwangmu, particularly in later Han dynasty imagery that reflects evolving associations with the moon and immortality.This visual pairing reflects a deeper mythological link between Xiwangmu and lunar symbolism. In Chinese cosmology, the West is associated with the moon and autumn, in contrast to the East and the sun. This duality is reinforced by narratives from texts like the Huainanzi, where the Queen Mother grants the elixir of immortality to Hou Yi. After Chang’e steals and consumes the elixir, she ascends to the moon accompanied by the Jade Hare, which later became a widely recognized symbol of longevity. As a result, Xiwangmu, being the original keeper of the elixir, became intimately connected with the moon and its mythical resident, the Jade Hare.

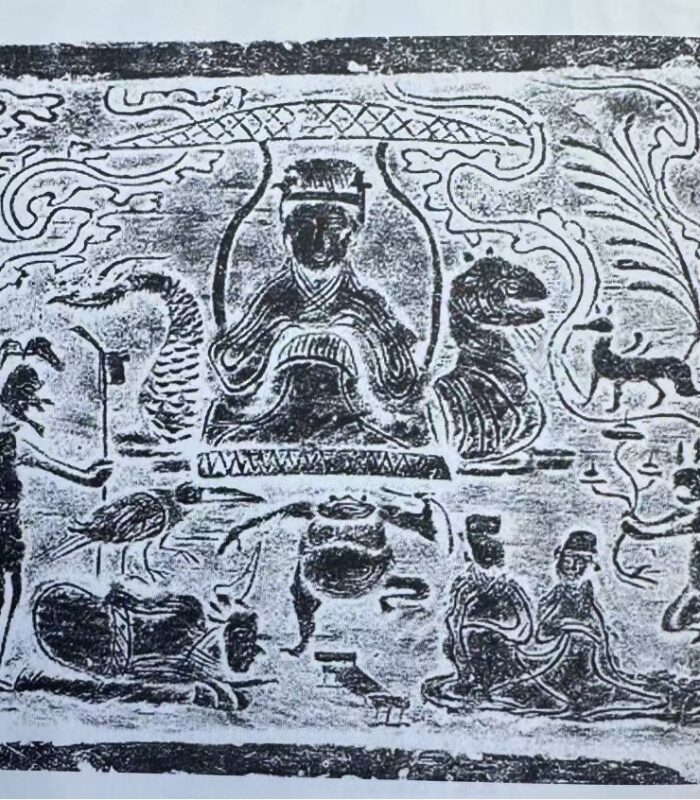

In the Xin Mang Tomb mural, the Queen Mother is shown seated on a cloud, wearing a sheng headgear and gazing solemnly at a jade hare positioned to her right. The hare, depicted with large ears and wings, kneels before a tall mortar and raises one paw mid-air as it pounds medicine—a gesture directly referencing its legendary role in preparing the elixir of immortality. The prominence of the hare in the Xinmang tomb mural, shown actively pounding medicine, further reinforces the Queen Mother’s role as a divine bestower of immortality and cosmic balance.

· Toad

The toad is another symbolic creature closely associated with Xiwangmu, particularly in Han dynasty visual culture, where lunar imagery and motifs of immortality take center stage. Like the hare, the toad is linked to lunar mythology and plays a role in reinforcing the Queen Mother’s connection to the moon and the celestial realm.

In Daoist lore and texts such as the Huainanzi, the moon is home not only to the jade hare but also to the toad, both of which are often depicted together in immortality-themed art. The presence of the toad in the mural, therefore, adds a further layer of meaning—symbolizing transformation, longevity, and the mysterious powers of the moon.

· Nine-Tailed Fox

The Nine-Tailed Fox is a significant symbolic creature associated with Xiwangmu, particularly in Eastern Han tomb murals where it often appears at her side. While the fox’s multiple tails are not always distinctly depicted, flowing tail is visible. Scholars generally interpret this figure as a nine-tailed fox, a creature rich in mythological meaning.

The tail itself is a symbol of fertility in ancient Chinese culture. The fox’s long, bushy tail embodies ideas of sexuality, reproduction, and the cyclical nature of life. At the same time, the nine-tailed fox also carries associations with death and the underworld. In the Shan Hai Jing, the fox is said to dwell in Youdu, a mythical underworld realm or burial space, linking it to themes of mortality and tomb culture. This dual symbolism—of both death and fertility—resonates deeply with Xiwangmu’s own divine identity. As a goddess who governs both the decline of life and the promise of immortality, the fox serves as an ideal companion, visually reinforcing her complex role as a deity presiding over both ends of the life cycle.

· White Tiger

The White Tiger is one of the earliest and most potent symbolic animals associated with Xiwangmu, closely tied to her mythological origins and fearsome divine authority. In the Shan Hai Jing, she is described as having tiger-like teeth and, in some versions, even the body of a white tiger with stripes and a tail, suggesting a hybrid form that emphasizes her otherworldly power and untamed nature. These descriptions reinforce her early characterization as a formidable, even terrifying deity who ruled over calamities, cosmic retribution, and the boundaries between life and death.

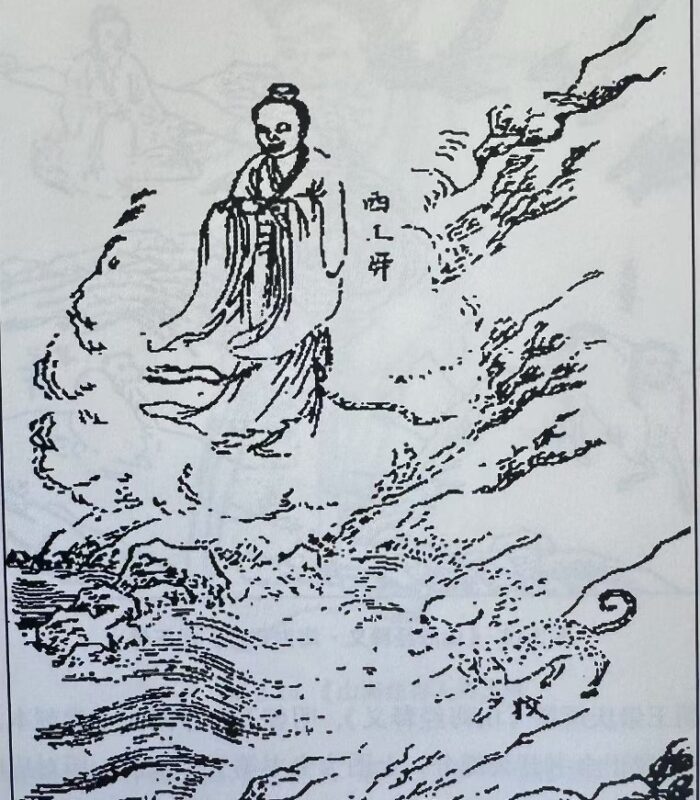

Further textual references, such as in the Mu Tianzi Zhuan, also allude to a realm filled with tigers and leopards, where the Queen Mother resides. In one of her poetic exchanges with King Zhou Mu, she invites him to stay in a land “where tigers and leopards abound,” using this imagery to underscore the wild, sacred, and liminal quality of her western domain. In artistic representations, the image of the tiger appears more frequently as her mount.

Later interpretations, especially within Daoist iconography, often depict the White Tiger as one of the four directional guardian beasts (symbolizing the West and the element of metal), which further aligns it with the Queen Mother’s domain. In some Daoist paintings and texts, the White Tiger serves as her mount or attendant creature, reflecting her integration into a structured celestial order while preserving echoes of her ancient, untamed power. Thus, the White Tiger becomes both a symbol of her primal origins and a testament to her enduring authority over the western heavens, judgment, and transformation.